Utilitarianism II

1. The Almanac. An objection to Mill is that we don’t know the future well enough to figure out what is “expedient”, i.e., what in the long run maximizes utility. Moreover, we don’t always have the time to figure it out. Mill responds in chapter 2 with his “nautical almanac” story. For navigation, we need to know positions of celestial objects by date. True, one could calculate them oneself using Newton’s laws, but that would take a long time. A nautical almanac contains pre-calculated positions of stars and planets. That one uses an almanac does not put into question the basic nature of Newton’s laws. Likewise, we have an ethical almanac: the consensus of humankind. People over the centuries have worked out what maximizes utility, and have devised ethical rules that are useful “rules of thumb”, such as “Thou shalt not give false witness”.

- Of course Mill thinks there are exceptions to at least some of these rules, namely cases where following the rule does not maximize utility. Thus, if one is hiding Jews in one’s basement, one does not maximize utility by telling the truth to the Gestapo officer. In such an exceptional case, telling a lie is the morally right thing to do according to utilitarianism. But a utilitarian like Mill would insist that we have to be very cautious in going against the rules humankind has worked out. There is a good chance we’re wrong, after all.

2. Justice. People tend to believe that over and beyond expediency, there is justice. The rules of justice outweigh those of expediency. Mill argues that justice is actually grounded in utility-maximization. Here’s why.

- There are six different notions about justice/injustice that commonsense has:

- It is an injustice to violate the legal rights of someone.

- It is an injustice to violating the moral rights of someone. There are many views on when one can disobey state law. Most of them say that when state law is unjust, we can disobey. The one exceptional view is that we should obey the law always because not doing so produces chaos. Note that the people who hold this exceptional view are making a utilitarian argument.

- It is just to give people what they deserve. Reward and punishment.

- It is unjust to go against a commitment.

- It is unjust to be partial.

- We should be equal.

- Mill is going to show that these six notions can be made sense of within a unified utilitarian framework. He thinks that all of these notions have common to them the idea of a law, either a law that exists or that should exist. Thus, he considers the idea that injustice is doing of something that should be punished, the violation of a law that ought to exist. However, all morality has that property.

- To make a further distinction, Mill brings up the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties. He thinks that violation of a perfect duty is injustice, and this is when one has gone against the right of a specific (“assignable”) person. What is a right? One has a right to a good (or to the absence of something bad) provided that society ought to defend one in the possession of the good.

- Thus, all immorality is something society should be defended from. But not all moral considerations involve some assignable person’s rights. Thus, it is immoral on utilitarian grounds to be lazy and to fail to develop one’s talents. But no assignable person’s rights are violated here. (Maybe God’s? But Mill’s ethics leaves God out.) While punishment is appropriate, there is no specific person whom punishment would defend in such a case.

- On the other hand, if I give false testimony, there is an assignable person whose rights I have violated: the person against whom I give false testimony, and the court to which I give it. If more generally I lie, in most cases I have violated your right not to be deceived. Society ought to defend such rights. (Of course in most cases of private lying the defense should not be through “the law”, but through rebuke, social ostracism, cold looks, etc.)

- [Objection to the idea that injustice involves an assignable person. Suppose that I deliberately release a rabid dog in a city so that it would bite someone. Clearly this is unjust—I should be thrown in jail for assault. But suppose I do not care whom it bites. Suppose in fact the dog bites no one. Whose rights have I violated? There does not seem a single victim—I’ve equally endangered everyone around there. Maybe then the “assignable victim” is everyone around there. But if so, then likewise, if I do not develop my talents, somebody is harmed by it, someone who could have benefited from my development of my talents. It is not clear who this person is, but everyone is harmed in seemingly the same sense as in the case of the dog—there isn’t a clear person whom my talents would have benefited, so we reify the people harmed into an “everyone”.]

- But [even if the above objection is answered] there is something left undefined so far. How do we tell what society ought to defend one in the possession of? Easy! This is utilitarianism. Thus, what anybody—including society, it seems—ought to do is to maximize utility. Hence, x is one’s right if and only if societal defense of one’s possession of x maximizes utility.

- What makes lying in most cases wrong is that it decreases human happiness, e.g., by decreasing the trust between people that is needed for a harmonious society. What makes it not just wrong but unjust is that society ought to defend you from being deceived by me. Why? Because such a defense maximizes utility. If society imposes penalties on liars, most especially the penalty of ostracizing them from the company of people who are trusted, utility is greater than if such penalties are not imposed.

- But in exceptional cases, such as of the Gestapo officer, imposing a penalty on the liar does not maximize utility, since it encourages people to turn Jews in, and the suffering of these Jews greatly decreases utility as opposed to the non-imposition of a penalty. Hence, such a lie is neither unjust nor immoral if utilitarianism is true.

- The above argument for a utilitarian account of justice has the following structure: The various kinds of justice/injustice become unified by seeing them all as instances of violation of rights, and seeing the violation of rights as rooted in considerations of what it is expedient to punish completes the theory, while accounting for “exceptional” cases. Thus, utilitarianism provides a comprehensive and simple theory of justice.

3. The argument from applications.

- Mill has a second argument for a utility-based account of justice. Consider various cases where it is not clear what justice says. E.g.:

- Should we pay workers proportionately to effort or output?

- Should we punish people to deter others, to improve the people themselves, or not at all?

- Should we tax people all at the same percentage, or the rich at a higher percentage, or should everyone get the same lump sum tax?

- In each of these cases, it is very hard to tell what the right answer is based on intuitive notions of justice. But once we consider utility, then, even if we do not see what the answer is, we know how to figure it out—we need to use economic theory. And some things are clear. If everyone is taxed the same lump sum, there will be a lot of misery since the poor will have to starve as they won’t be able to afford the lump sum. If we do not punish people at all, crime will multiply and people will be miserable. We might add: Effort is hard to measure, so paying workers proportionately to effort will boil down to paying them proportionately to apparent effort, and they’ll try to fake effort, which is bad.

- An opponent to the argument from applications might either strive to find a principled answer to the questions, or might say: “Yes, in these cases the considerations of justice are balanced. Hence we must employ utilitarian considerations as a tie-breaker. This does not mean justice is grounded in utility, but that utility is a tie-breaker.”

4. The abhorrent conclusions objection to utilitarianism.

- Case A. You are the judge in a no-jury trial of a man you know to be innocent. If you do not sentence him to death, there will be a riot and many will be killed. It seems that it maximizes utility to sentence the innocent man to death.

- If it is wrong to sentence the innocent man to death and if it maximizes utility to do so, then utilitarianism is false.

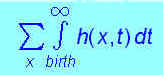

- However, the utilitarian will say that when we look

at total human happiness, we look at all human happiness from now into

the future. (

, where h(x,t) is the happiness of

person x at t and the sum is over all people). Sentencing the

innocent man to death will decrease people’s trust in the law, increase

vigilante justice, and encourage future mobs.

, where h(x,t) is the happiness of

person x at t and the sum is over all people). Sentencing the

innocent man to death will decrease people’s trust in the law, increase

vigilante justice, and encourage future mobs. - Case B. As a surgeon, by killing a woman coming in for an appendectomy, you can ensure the availability of organs that would save the lives of three people who would otherwise die. If all of the four people have equally good prospects for a happy future, it seems to maximize utility to kill the patient and use her organs.

- If it is wrong to kill the patient and it maximizes utility to do so, then utilitarianism is false.

- Again, the utilitarian will say that in the long term, utility would not be maximized. People will become more afraid of hospitals, the surgeon might get caught, life becomes cheapened in the surgeon’s eyes and she becomes a less good surgeon, etc.

- In both cases, the utilitarian will likely insist that in the long-term, the killing will produce lesser utility. Mill will add that this is why we have such a strong commonsense opposition to killing—over the centuries we’ve figured out these utility considerations and found that any killing of the innocent is non-optimal vis-à-vis utility.

- The anti-utilitarian does, however, have two responses to the “long-term” considerations.

- The “one thought too many” response. Saying that in these cases utility is harmed in the long run is one thought too many. It’s not the real reason it’s wrong. The reason it’s wrong to kill the patient or sentence the innocent person to death is that it is the killing of an innocent person, not that it will produce all kinds of bad consequences for other people after the person dies. It is the harm to the victim, and maybe to the victim’s friends and family, that makes the killing wrong, not long term consequences for others. The latter consideration should not even come up.

- The cases can be tweaked so that the long-term consequences aren’t like that.

- Case A*. Suppose the judge alone knows a crucial piece of evidence that exonerates the accused, and without this evidence there is an overwhelming case against the accused. The judge in fact saw the accused miles away from the crime. If the judge says this, the mob won’t believe him. Nobody knows that the judge saw the accused. The judge holds back this crucial piece of evidence and convicts the man. Since everyone thinks the accused is guilty, people’s trust in justice will be reinforced by sentencing him to death. Suppose for instance that the judge and the accused are members of a racial minority. Then, acquittal might lead people to question justice (and people won’t believe the judge’s testimony) because they’ll think the judge acquitted the man because they are both members of the same race. In this case, the long-term consequences are better if the man is convicted.

- Again, the objector to utilitarianism insists that even in this case, it is wrong to convict the man.

- Case B*. Suppose that the surgeon knows she can get away with it. She can do it while the nurse is out of the room, and no one will know. Moreover, she knows that the negative publicity for the hospital from this death will be outweighed by the positive publicity from the three transplant operations. And she is not worried about her own attitude towards life worsening, because she is retiring the next day anyway.

- Again, the objector to utilitarianism insists that even in this case, it is wrong to kill the patient for her organs.

- Note that the second form of the Categorical Imperative handles these cases much more intuitively. In these cases, one person is being used as a mere means. Such use is wrong.