1. Is marriage a covenant or a contract?

- A related question is whether

marriage is good in and of itself, or only insofar as it helps the

individual members of the couple achieve particular ends. If the latter, it is more likely that marriage

is a contract. If the former, then

it is more likely to be a covenant.

- If marriage creates a new,

morally significant united being—say, via a joint identity—then there is a

value in the couple as a whole, and

there may be a reason to keep the marriage together for the sake of the

united being even when neither party presently wants that. This is more like a covenant.

- Odysseus and love.

2. Aristotle thought that virtue was always a mean between

two extremes, a mean chosen with reason. Thus, the courageous

person is someone whose fear avoids the extremes of cowardliness and

foolhardiness. The generous person is someone who avoids stinginess and

profligacy. And so on. We do not, of course, just look at the

two extremes and choose amen halfway. We use reason to decide where the appropriate

place for the virtue: in the virtuous person the emotion, quality or action has

the appropriate degree, neither automatically maximized nor

automatically minimized (and perhaps on occasion, an emotion might be

appropriately maxed out—that is not the extreme, as the extreme is to have the

emotion to a maximum degree always).

·

William May uses this

kind af framework here.

·

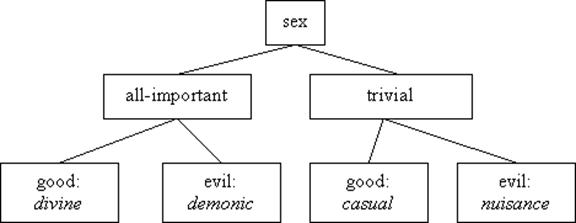

If we think of sex as

all-important, we are likely to see it as divine or demonic. If we think

of sex as trivial, we are likely to see it as casual or a nuisance. Each

of these views is mistaken, for different reasons.

·

The right view, on

Aristotelian principles, will make sex be somewhere between the all-important

and trivial. Nonetheless, there may be something to each of these

views. (Just as there is something to the idea of fearing always and

fearing never—the courageous person has a mix of fear and fearlessness

according to Aristotle.) Sex is important, and yet not too

important. It is originally good, May thinks, but can lead to evil.

·

Let us suppose, with

much of our culture, that sex is good.

·

Why isn’t

sexual-important? May thinks that if someone makes sex all-important and

good, i.e., divine, then sex will fail to deliver on this expectation, and

the person will suffer from disappointment, and the person’s partner will

suffer for failing to deliver.

·

Why isn’t sex trivial

and something to be taken casually? May suggests:

·

We have a fascination

with sex. There is something to the idea of sex as divine, as

having about it something of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans that

Rudolf Otto talked about. Sex wouldn’t sell magazines, etc., if sex

weren’t something important to us.

·

Given a book with a

number of chapters, if “sex” is one of them, people will turn to it.

·

The “sex as casual”

theory is based on the idea of our bodies as raw materials that we can do with

what we like. May clearly thinks, at least on theological grounds, that

this ideas a false one.

·

The theory “lapses

into akin of emotional prudery”, in that it forces us to deny much of our

sexuality, namely “affection, … loneliness …, jealousy, envy, preoccupation,

restlessness, anger, and hopes for the future” (p. 196). Prudery is a way

of pretending we do not have sexual interests. But if we deny many of the

emotions that are a part of human sexuality, we are still prudes, May thinks.

·

Additional arguments

can beamed for the non-triviality of sex. For instance:

·

If sex were something

entirely casual, something devoid of intrinsic importance, why would rape be

smooch worse than a non-sexual assault that produces comparable physical

damage?

3. May, instead, thinks on theological grounds that human

bodies are a good thing, created by God, and so is sex. He thinks that

because sex is good and important—though not all-important—it requires discipline,

i.e., ways of restricting ourselves in order to train us to use it well.

The need for restrictions does not imply that the thing restricted is

evil. For instance, we should put restrictions on our minds—forcing

ourselves not think fallaciously—precisely because our minds are too good to

waste bethinking unclearly.

4. William May says that sex is a gesture. The “human community suffers strains” when gestures stop matching their inner reality. (There is something particularly evil about a smiling villain.) The gesture of sex signifies commitment. But the commitment is not there. So things are dishonest.

· But what if the members of the couple explain to each other that the gesture lacks its usual meaning? (Do they in fact do that? Do two people very often think that the sex lacks its meaning of commitment—do they simply cynically seek pleasure? Or is there almost always a little bit more?) May says that this can often sound false note. It is awkward.

o Think there is a deeper problem. If we keep on using a gesture to mean something else than what it normally means, then the gesture loses its meaning to us. If I keep on smiling all the time for no reason at all, the smile becomes meaningless. The boy who cried wolf! If we use sex in a way that does not mean total commitment, a union of two persons until death, then it stops having that meaning to us. But once it stops having that meaning to us, then we no longer have anything as appropriate to express that meaning. Should we then come upon the love of our life and marry, we would no longer be able to use sex to express the committed love—for it would no longer have that meaning to one. Or at least that meaning will be weakened.

· Secondly, love asks for a continuance of love. Single act of lovemaking is incomplete. It calls for a future development. And thus there is something definitely lacking when it occurs in a context where the future development is not planned.

5. Punzo considers the following argument against premarital sex. He starts by insisting that sex is important. It is not like going to a movie with someone or sharing some ice cream with someone.

· Is he right?

o Consider rape. It is surely a very different thing to be raped than to be forcibly taken to see a movie or made to eat some ice cream with someone.

o People don’t usually feel betrayal in the other contexts. “He shared ice cream with me today, and tomorrow he shared it with someone else.”

o Aloof us think that there are various restrictions on sexual activity. For instance, we think it is wrong to engage in it with children, dead people or animals. There is nothing wrong with someone offering ice cream to child or to a dog. If we heard that the mortician put some ice cream in the corpse’s mouth, we would think he did something weird and disgusting, and should clean it up, but we would feel very differently if the mortician had sexist the corpse.

o Why is sex different in this way from other activities? This will be a question that we are going to be thinking about for a long time. But we won’t be far off from the truth if we say that sex is more intimate, a deeper union between people. Sex is something significant to human person. One might even say that sex is in some sense something sacred.

· Punzo thinks that sexual intercourse is the most thorough possible union of two bodies. It is not simply giving pleasure to another person or to oneself. It is uniting one body with another.

· But we are not only bodies. We are not animals. We are persons. If we unite our bodies in the most thorough way possible without being correspondingly united as persons, we are treating our bodies as mere objects. We are alienating ourselves from our bodies. And we are deceiving ourselves. We are “depersonalizing” our bodies.

· But the kind of union as persons that Punzo thinks needs to be present is likewise the most thoroughgoing union we are capable of: a union for life. Because the sexual act unites the bodies, and because the bodies are supposed to express the persons, the persons had better be united. Their lives need to be one. Otherwise, the sexual act is in and of itself a lie.

· The life of a human being “involves his past and his movement toward the future.” This movement toward the future needs to be united with another person’s movement toward the future for the union of their bodies to be honest. Only then “The total physical intimacy of sexual intercourse will be an expression of total union with the other self on all levels of their beings.”

6. Punzo on ceremonies… Punzo thinks that a couple counts as married even before the wedding ceremony. The ceremony only makes public a private commitment.

· But is there really such an unconditional commitment prior to the ceremony?

· One might think that a commitment of this sort requires solemn promise, and it is at the wedding ceremony that this is exchanged.

· Moreover, if the commitment were there already, wouldn’t it follow that the guests and witnesses are deceived, because they think they are witnessing the making of the commitment, but they are not?

· A thought experiment. One finds out that one’s beloved had in the past murdered his father. He hasn’t changed very much as a person, either, and is quite unrepentant, but you are pretty sure he won’t do it again. He hated his father intensely, and doesn’t hate anybody else with equal intensity, and is only going to kill someone he hates so intensely. So you’re not afraid of living with him.

· Depending on whether you’ve gone through the ceremony or not, your attitude will be different. In either case, you might end up breaking up. But if you break up before the ceremony, you will have feelings of relief: “I am glad I didn’t marry that creep!” If you break up after the ceremony, it will be much more painful. Moreover, you will be more likely to stay together with the person if the ceremony has happened. One feels that one should break up if it’s before the ceremony. But after the ceremony, things are different. This shows that there is a difference in the level of commitment.

7. An argument I got from, I think, Kaczor:

1. It is wrong to take on a significant risk of being in a position where one is unable to fulfill central responsibilities to one’s child except for the sake of something objectively very important.

2. Sex carries a significant risk of pregnancy.

3. A person, especially a man, who has a child while not married runs a significant risk of not fulfilling central responsibilities to one’s child.

4. Sex outside of marriage does not achieve something objectively very important.

5. So, sex outside of marriage is wrong.